Artículo de investigación

Teacher Strikes and Private Education in Argentina

Huelgas docentes y educación privada en Argentina

Greves docentes e educação privada na Argentina

Mariano Narodowski*

Mauro Moschetti**

Silvina Alegre***

* Doctor en educación de la Universidad Estatal de Campiñas. Profesor de educación en la Universidad Torcuato Di Tella. Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina. Correo electrónico: mnarodowski@utdt.edu

** Postgrado en Educación de la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. Profesor asistente en la Universidad de San Andrés. Buenos Aires, Argentina. Correo electrónico: mmoschetti@udesa.edu.ar

*** Doctora en Ciencias Sociales de la Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO). Profesora asociada a la Universidad Nacional Arturo Jauretche y consultora en la Organización de Estados Iberoamericanos (OEI) Correo electrónico: slvnalegre@gmail.com

Recibido: 03/08/2015 Evaluado: 22/09/2015

Abstract

This article analyzes teacher strikes in Argentina during 2006-2012. It stands out how teacher strikes prevail over claims from other unions, and are shown to be relevant events for education policy just for some provinces and only for public schools. We found that none of the policy measures implemented over the last decade has proven to be effective in reducing conflict. Analyzing a dataset on labour unrest, this study builds an index of teacher labour conflict to better understand the evolution of teacher strikes over time and under the various provincial governments that integrate the Argentinian federal education system. The article shows no correlation between teacher labour unrest and the growth of private enrolment. However, we note that despite the lack of statistical correlation, teacher strikes should not be ruled out as an explanatory variable of the increase in private education in Argentina.

Keywords: Argentina, education policy, private education, public education, teacher strikes.

Resumen

Este artigo analisa as greves docentes na Argentina para o período 2006-2012. Destaca-se como as greves de professores prevalecem sobre os reclamos de outros sindicatos, e constituem eventos relevantes só para algumas províncias, e só para as escolas públicas. Adverte-se que nenhuma das medidas de política educativa aplicadas no período, tem sido eficaz na redução de conflitos. A partir da análise de um conjunto de dados sobre conflito do trabalho, o estudo constitui um índice de conflito docente (TCI) para compreender melhor o comportamento de graves de professores no tempo, e baixo os distintos governos provinciais que integram o sistema educativo federal argentino; a análise mostra que não existe uma correlação entre o conflito de trabalho docente e o crescimento da matrícula particular. Por último, advertimos que a pesar da falta de correlação observada, o conflito de trabalho docente no deve descartar-se como variável explicativa do aumento da educação particular na Argentina.

Palabras clave: Argentina, política educativa, educación privada, educación pública, huelgas docentes.

Resumo

Este artigo analisa as greves docentes na Argentina para o período 2006-2012. Destaca-se como as greves de professores prevalecem sobre os reclamos de outros sindicatos, e constituem eventos relevantes só para algumas províncias, e só para as escolas públicas. Adverte-se que nenhuma das medidas de política educativa aplicadas no período, tem sido eficaz na reduço de conflitos. A partir da análise de um conjunto de dados sobre conflito do trabalho, o estudo constitui um índice de conflito docente (TCI) para compreender melhor o comportamento de graves de professores no tempo, e baixo os distintos governos provinciais que integram o sistema educativo federal argentino; a análise mostra que no existe uma correlação entre o conflito de trabalho docente e o crescimento da matrícula particular. Por último, advertimos que a pesar da falta de correlaço observada, o conflito de trabalho docente no deve descartar-se como variável explicativa do aumento da educação particular na Argentina.

Palavras chave: Argentina, política educativa, educação particular, educação pública, greve docentes

Introduction: Private Education in Argentina

The Argentine education system has experienced a long-standing process of privatisation with private school enrolments growing both in absolute and relative terms over the last fifty years. Early works on the subject have showed the singularity of the Argentine case fifteen years ago (see, for example, Narodowski & Andrada, 1999 and 2001; Morduchowicz, 1999.) This pro-N °70 cess of privatisation of education, which began in the 1960s, has experienced an important increase since 2003, becoming an unprecedented phenomenon in the history of the country (Narodowski & Moschetti, 2014.)

Argentina is a country with a federal political administration, which presents 24 provinces that administer their own educational systems, with national policy coordination and some federal education funding. Differences between provinces are very important in terms of area, number of inhabitants, gross product, type of economic activity, and party and political organization. For example, while in the City of Buenos Aires the cdp per capita in 2011 reached $127,997, in the province of Santiago del Estero it amounted to only $8,285 (IEE, 2012).

Despite these noticeable differences, in 23 out of the 24 federal jurisdictions, the number of private school students has grown more than the number of students in public schools for all levels-kindergarten/pre-school, primary and secondary education-. During the period 1996-2012, in provinces such as Tierra del Fuego, Jujuy and Catamarca the enrolment in private schools has increased in 106, 90 and 88 percentage points respectively above enrolment in public schools (Narodowski & Moschetti, 2015).

Even though it is true that during the years of the big economic crisis in Argentina (2001-2002) the enrolment in private schools shows a slight decline (-0.4%), between 2003 and 2012 it increased by 20% for the three levels of the education system (Narodowski & Moschetti, 2015).

Taking as a starting point the year 2003-the first year after the socioeconomic meltdown and the early administration of President Néstor Kirchner followed by President Cristina Kirchner1- primary private education has grown by 22 % until 2011, while public primary education has lost 6 % of its enrolment. According to official data, in 2003 70 % of primary school students from Greater Buenos Aires attended a public school; in 2011 it was reduced to 60 %. Provinces like Catamarca, Jujuy, La Rioja, Santa Fe and Mendoza have lost more than 10 % of their public primary school students, and Santa Cruz 15.2 % (Narodowski & Moschetti, 2015).

As for the other levels of the education system, in kindergarten/ pre-school/early education (schools that admit children up to 5 years of age) the total amount of students grew by 17.7 % but at a rate of only 11.3% for the public sector and 34.4% for the private sector. In secondary school, total enrolment grew. Public enrolment grew by 6 % and private by 10.6 %.

This growth in the number of students is endorsed by the financial support on behalf of all provincial governments to private education; a policy of supply-side subsidies (aimed at funding teacher salaries) that private schools have been receiving for half a century. Data show that subsidies to private education have remained stable and accompanied the growth in enrolment (Moschetti, 2013).

For a long time, it was believed that this process of privatisation of education was the effect of neoliberal educational policies implemented in the 1990s (Puiggrós, 2003; Torres, 2008). However, a recent work has shown that the growth of private education enrolment corresponds to long periods spanning from education policy efforts of both "neoliberal" and "post-neoliberal" governments (Narodowski & Moschetti, 2015). In fact, since 2003 and with governments against neoliberal policies, private education has grown in an unprecedented way in the history of Argentina.

Within the explanatory framework of the growth of private education, the idea that successive and massive teacher strikes are causing the movement of families from public to private schools is a common-sense assumption of the media and the political and academic debate, despite the lack of studies that confirm so (Bottinelli, Herrera, Almirón & Stegman, 2013).

The purpose of this study is twofold. First, it attempts to analyze the behavior of teacher strikes in Argentina, both nationally and at the provincial level, considering their prevalence in relation to claims from other unions and their relative weight in each educational jurisdiction. Second, the study aims to find whether there is an association between class days lost due to teacher strikes and the growth of enrolment in private schools.

This article is structured as follows. We first describe the functioning of the Argentine education system by means of the notion of quasi-State monopoly as a way of understanding the interaction between public and private provision over the last decades. We then offer a review of the most relevant studies that conducted research on educational labour conflict both in Argentina and other countries. Then, we provide an in-depth characterization of the teacher strikes phenomenon in Argentina between 2006 and 2012 and present an index that enables the comparison of its magnitude between educational jurisdictions. Section 5 explores the linkage between teacher strikes and the growth in private enrolment. Finally, Section 6 draws on some conclusions and offers general policy implications for the case.

Private School Choice, Teacher Strikes and Quasi-State Monopoly of the Education System

There is little evidence regarding the reasons for the exit from the public sector and moving to the private sector in Argentina. The latest study on this topic found that teacher strikes and loss of school days are one of the causes of exit stated by parents of different social sectors, although it is neither the only one nor the most important (Scialabba, 2006). This study also confirms that 33 % of parents with children in public schools would switch to a private institution if they had sufficient financial resources to do so.

Recent studies have also shown that private school choice is positively correlated with the existence of extracurricular activities in the private sector, which are infrequent or not offered at all in public schools (Gertel, Cámara, De Cándido & Gigena, 2013).

Some research show that the increase of private school choice is a result of segregation processes and especially socio-economic self-segregation. These processes are not exclusive to the middle class (Tiramonti & Ziegler, 2008); even the social sectors with fewer resources exit the public school as a means of distinction regarding upward social mobility (Gómez Schettini, 2007).

To provide a structural explanation of this process, Narodowski developed the notion of quasi-State monopoly, in an attempt to understand the interaction between public and private supply structures (Narodowski, 2008; 2011). The core of this framework presents the conceptualization of a classic work by Jean D'Aspremont and Jaskold Gabszewicz (1985). These authors analyze the situation in which, due to the steady increase in demand, an existing monopoly structure enables the generation of a new closed supply structure, provided that this is limited. It means that it captures only the excess demand that the old monopoly cannot absorb because of its various structural restraints, which do not allow full coverage of the demand. On this condition, the new sector does not directly compete with the traditional monopoly, but rather contributes to its continuity by providing coverage where the old State monopoly is not capable of doing so. Thus, the old monopoly can continue to operate on its captive demand, while it opens the opportunity for the development of a new supply sector.

The complete structure, that is, both the old traditional monopoly and the new supply structure, is called "quasi-monopoly". In line with previous works (Narodowski, 2008, 2011) and in direct reference to Hirschman's classic work (1970), the old monopoly has been called the "traditional sector" (since it refers to the predominant modality in the organization of the schooling supply where provision is entirely public) and the new sector, "exit sector", composed of private schools (some of which receive State funding)that capture those who abandon the pre-existing structure of educational supply.

The Argentine educational system scenario can be summarized, then, with the description of a quasi-monopoly (Narodowski, 2008). On the one hand, there is a traditional sector of schooling, monopolized by the State and formed by public schools, which serves mainly the lower-income households. On the other hand, there is an exit sector of private schools that is functional to the State sector in terms of efficiency of government expenditure. These private schools usually serve middle and high-ses households and have greater leeway to define and structure their own school projects following a 'school-based management' rationale (Gasparini, James, Serio & Vázquez, 2011; Nar-odowski, Gottau & Moschetti, 2013). In line with the studies cited above, it is possible to conjecture that the behavior of each sector can be explained by the operation of the whole; i.e. by the inclusion of new students to the educational system, by the regulation and funding of the State, and by the general economic and social conditions in which these actions occur. Thus, the concept of quasi-monopoly provides understanding of the fact that the increase in enrolment in private education in Argentina is not the effect of a "withdrawal", "weakness" or "disappearance" of the State, but of a conversion of its actions. This involves moving from a monopolistic administration of the school system to a more complex kind of administration that helps ensure the quantitative growth of the educational system, not in the traditional way by increasing enrolment in public schools, but combining and balancing its growth with that of private schools.

Teacher Strikes as an Educational Problem

Teacher strikes are a recurring topic in the Argentine education debate (Botinelli, Herrera, Almirón & Stegman, 2013). It is usually pointed out that the loss of school days due to strikes generates low educational quality, hinders continuity in studies, tarnishes the institutional image of the schools in which these measures are taken, and increases enrolment in private schools (since strikes occur almost exclusively in public schools), among other consequences.

However, the absence of studies on this issue is certainly remarkable. This is one of the allegedly "hot spots" in the media agenda dedicated to education, but such concern does not seem to be reflected in the agenda of studies and academic or technical research, where the impact of teacher strikes in the education system has been rarely addressed.

Some classical studies have shown the relationship between teacher working conditions and the quality of education (Narodowski & Narodowski, 1988; Narodowski, 1990). Other recent works have shown teacher strikes emerging as a way to resist political or pedagogical education reforms (Gentili, Suárez, Stubrin & Gindin, 2004). In this sense, the work of Murillo and Ronconi (2004) has shown the enormous political influence of teacher strikes, and how, in this scenario, Argentine teacher unions have built political power. Current studies have looked into the social characteristics of teachers (Donaire, 2009) and have even quantified strikes in Argentina, but for the purpose of confronting them with strikes from other worker unions (with the database on social protests of the Research Program on Argentine Society Movement) or with other databases (Chiappe, 2011).

Regarding legal analysis, Bravo presented legal and jurisprudential evidence concerning the conflict between the constitutional right to strike (for teachers) and the constitutional right to learn in institutions where teacher strikes occur (Bravo, 1996), given that teacher strikes are allowed in Argentina, unlike in other countries (Belot & Webbink, 2010).

International literature does not provide much evidence on the subject, except in some Latin American studies. Martin Carnoy (2005) illustrates the Argentine case in this way:

In Argentina, a highly developed country in many ways, elementary students attend school for an average of four hours a day, or less than 750 hours a year. However, the absences of teachers are relatively common in many provinces, and many days during the year are lost in strikes by teachers. (Carnoy, 2005, p. 8)

As a consequence -the author explains- the quality of education declines, in spite of the teachers' 'good intentions': "The main losers in the game that protects existing interests are children at the bottom of the social scale" (Carnoy, 2005, p. 11.)

Other studies have tended to estimate the impact of the action and the strength of teacher unions in educational policy measures, in the regulations of the education system, especially those related to the administration of teachers as human resources. Hoxby's article (1996) was a pioneer in showing how the unionisation of teachers has reduced productivity and has had a negative impact on student performance.

From that article onwards, there have been other investigations (Belot & Webbink, 2010; Lott and Kenny, 2013; Moe, 2011; Murillo, 2012 among the most recent ones) which have provided evidence or have discussed some issues related to the validity of the inference that connects the action of the unions with the "products" of the school system, such as student performance. However, teacher strikes in these studies are not particularly differentiated from actions taken by other unions and, therefore, its consequences (especially the actual loss of class days for students) can only be assumed in an indirect way. A different view on the impact of neoliberal reforms on education systems from the perspective of teachers' work can be found in Sinclair, Ironside and Seifert (1996).

Some other works have done research specifically into teacher strikes. Miriam Shenkar and Oded Shenkar's article (2011) analyses teacher strikes in the context of a work dispute in Israel and concludes that the formation of certain labour and social group identities are a component as well as a consequence of strikes. The phenomenon has been compared to similar studies in other countries: Athanasiades and Patramanis (2002) for the case of Greece, Carter (2004) for the case of England, Gaziel and Taub (1992) who compare Israel to France, among others.

In short, there is not much evidence in international academic research on the direct impact of teacher strikes on the dynamics of the educational system. For the Argentine case, there is a widespread assumption that they cause a number of negative effects: direct harm to students whose classes are suspended as a result of industrial action, which would contribute significantly to the choice of private schools by families. Notwithstanding the foregoing, until now there was no statistical evidence which seriously presented the consistency of this relationship.

Argentine teacher strikes inside out

To provide some explanations, we resorted to the database of labour conflict generated by the National Ministry of Labour and Social Security (Chiappe, 2011; Etchemendy, 2013). This database is produced on an annual basis and brings together all labour disputes occurred in the country in the period 2006-2012.

This official database records all the different types of labour disputes. It indicates the number of strikes by province, unfortunately it does not indicate the number of days covered by each walkout. N.°70 However, the database includes the record of a more interesting series of data than that of strikes, that of its quantifiable effect: the individual working hours not worked due to strike action.2

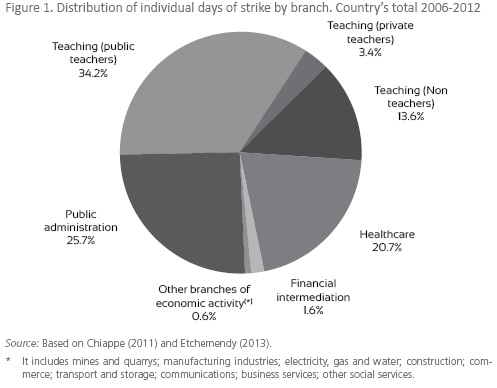

A first result of the analysis allows comparison between the importance of teacher strikes and industrial action in other branches of economic activity and employment in Argentina (Figure 1).

For the period 2006-2012, 51.2 % of the working days lost due to strikes in Argentina correspond to the education sector. Of these, 34.2 % correspond to public school teachers and only 3.4 % to private school teachers (while the remaining 13.6 % refers to labour disputes involving non-teaching personnel: administration, caretakers, assistants, etc.3) The other areas with high labour dispute ratio are public administration (25.7 %) and health (20.7 %), where State involvement is also prevalent.

Even if it is acknowledged that the number of teachers in Argentina is high (in terms of persons employed, teaching is the third branch of economic activity in importance, after trade, manufacturing and public administration) and that the graph of lost working days is influenced by the amount of work force employed, it is possible to infer that, in absolute terms, the strikes in Argentina are mostly bound to the educational sector and virtually hegemonized by public school teachers. Evidence shows that for the period 2006-2012, when referring to strikes in Argentina one is mainly addressing strikes in public educational institutions.

To illustrate this question, we present the annual evolution of the lost working days for the period 2006-

2012. This shows days lost because of teacher strikes in the State and private sectors of education in relation to other branches of activity (Figure 2).

As it can be seen, State teacher strikes show a differentiated behaviour with respect to measures taken by other workers: while strikes by workers in activities other than education peaked in 2008, teacher strikes that year show a decline. Conversely, in 2009 the level of teacher conflicts grew while conflicts in other industries decreased.

The graph illustrates a surprising element: working days lost due to teacher conflicts have an erratic behaviour, which does not allow make any inferences about a clear trend, neither upward nor downward. This phenomenon seems to show the ineffectiveness of public policies implemented by the Government aimed at moderating teacher conflict in Argentina. To this end, in 2004, Act 25,864 was passed which set a minimum of 180 school days per year (Art. 1). It further provided that

If the loss of school days has its origin in the inability, on the part in provincial jurisdictions, to afford wage debts to teaching personnel, be it for reasons of force majeure or for temporary cash flow deficiencies, they may seek financial assistance from National Executive Office, which will take immediate measures to respond to that effect. (Art. 3)

Additionally, the national government has set a starting salary (minimum revenue guaranteed per teacher) to be adopted compulsorily by all Argentine provincial jurisdictions to avoid differences among provinces. Moreover, in 2006, Act 26,075 on Educational Financing was passed. Its 10th article provides for the creation of a National Teacher Collective Bargaining to conduct the sector's wage negotiations. In this sense, as pointed by Rivas, Vera and Bezem (2010), between 1996 and 2008 the provincial average wage increased by 44.9 % in real terms. The Government announced in 2013 that the average salary of teachers rose between 2003 and 2013 more than 600 % (about fifty percentage points above the Argentine inflation rate for the period).

It would have been expected that after these regulations and measures of educational policy, school days lost due to teacher strikes would have tended to fall, but as can be seen in the graph, the enactment of the Law had no relevance whatsoever: teacher strikes increased in Argentina in the period 2006-2009, decreased between 2010-2011, only to resume in 2012 similar levels to those of 2008. Thus, it becomes clear that public policy has lost, during this period, the possibility of solving teaching conflicts either directly or gradually.

Moreover, we note that between 2006 and 2012 a total of 19,277,736 teacher workdays were lost, an average of 2,753,962 annual workdays. To statistically adjust lost working hours in each of the 24 jurisdictions, and because of the huge differences in size between them in relation to the number of students, teachers and schools, the original data base has been normalized to build a Teacher Conflict Index (annual TCI). The TCI is the ratio between the number of days not worked in each education sector and the corresponding enrolment, by province and year.

Table 1 shows the teacher conflict represented by the TCI in each of the jurisdictions in Argentina for the period 2006-2012. The table distinguishes between the TCI in the State sector and the private sector, indicating the percentage differences between them.

As it is shown, the issue of teacher conflict, even in public schools, varies enormously between provinces and shows that teaching conflict is not a problem across the country but a characteristic of some provinces. Furthermore, in half of the Argentine provinces the problem is very serious and many days of class are lost. In the other provinces, teacher strikes seem to barely constitute a real problem for educational policy, at least in comparison to other jurisdictions.

The reasons for the high TCI at certain times or in certain provinces are not tackled by this study. It is assumed that they have to do with the histories, situations and identities specific to each jurisdiction as well as the fiscal, wage, union and political situation. In fact, the analysis of the TCI should encourage research on teaching conflict dynamics.

Interestingly, none of the 8 provinces with greater TCI has a relatively high number of students in the educational system. In fact, the provinces with the highest TCI do not reach 20% of the school population of Argentina for the period, although the differences are deep (and unpredictable) year to year and province to province.

However, when looking at the table, the enormous differences between TCI in public and private education become evident. With this data it is possible to infer that the issue of teacher conflict and the loss of school days is a major problem for public education in almost every province, with the exception of Tucumán, La Pampa, Formosa, La Rioja and particularly San Luis, the only one out of the 24 jurisdictions where the TCI in public schools is very low and increasing in private schools.

Teacher Strikes and Enrolment Growth in Private Schools

Does the increase and decrease of teacher strikes have an impact on the enrolment growth in private schools? Figure 3 shows the evolution in private enrolment at the national level. An important and sustained increase is evidenced for the last nine years.

With the data collected, it is now possible to determine whether or not there is an association between lost school days due to strikes and the increasing number of students in private schools, both for each province and for the country as a whole.

Figure 4 compares the growth of private enrolment with that of the teacher labour conflict for the period 2006-2011.

While the growth of enrolment in private education shows a steady growth over time, the TCI shows significant ups and downs: the increased enrolment in private education post-2003 never stops, while teacher labor disputes increase and decrease.

Figure 5 shows the spread of the Argentine provinces in relation to the growth of private education enrolment and the Teacher Conflict Index.

The graph shows no significant association (R2=0.08) between the growth of private school enrolment and the TCI indicating class days missed because of teacher strikes.

In highly conflictive provinces private education has increased relatively (as in the case of the Province of Neu-quén) and conversely, provinces with less conflict have shown disparate behavior. In San Luis and La Pampa, days lost because of teacher disputes in the State sector remain low, while privatisation of enrolment increases abruptly. Meanwhile, in Chubut and Tucumán both State teaching conflicts and the increase in private enrolment are not significant. Therefore, the type of dispersion shown does not enable to identify covariance relationships. The cases of Santa Fe and Chubut are worth mentioning. During this period, in these provinces strike days decreased while the enrolment in private schools remained unchanged.

Conclusions

Statistical evidence shows, first, the importance of teacher strikes in Argentina, which hegemonizes the landscape of labor unrest. It also shows how public policy measures to mitigate their amount and frequency (salary raise, National Teacher Collective Bargaining, 180 days of class, etc.) have resulted not only insufficient, but did not even seem to have moderated teacher conflict over time, both at a national level and at least in a large group of provinces.

While the media's common sense attributes to teacher strikes a central role in the growth of private education enrolment after 2003, the evidence analyzed between 2006 and 2011 -a period of high teacher conflict as well as of great growth in the enrolment in private schools in every province, except for Santa Fe-clearly shows that it is not possible to predict an increase (or decrease) in enrolment in private schools from the occurrence (or not) of teacher strikes and the consequent loss of school days.

When facing the occurrence of more teacher strikes, it is not necessarily to be expected that there will be more students in private schools. Conversely, a decrease in the number of teacher strikes in no way would explain a virtual enrolment growth in public education. Therefore, the actions of teacher unions based on strikes and loss of class days are not relevant in terms of impact on the dynamics of the most important political/educational phenomenon in the post-2003 period that is the growth of the private sector of education.

This does not mean that the existence of teacher strikes in public schools does not influence the preferences made explicit by many families that choose private schools, as noted in Scialabba's study (2006). What has been shown here is that there is no association between the two variables for the period 20062011, but it has not been denied that there may possibly be a relation between them.

It is necessary to continue studying this issue to understand whether families that choose private schools assume teacher strikes as something of central importance, beyond their mere occurrence, and that this perception trascends periods and territories. Many social sectors may have assumed teacher strikes, and the consequent loss of school days, as a "natural" and inherent characteristic of the public school, even beyond what happens in objective reality.

Furthermore, this study has analyzed the working days lost in schools due to teaching conflicts, which accounts just for part of the days in which public schools remain closed or that students do not have classes. Other reasons may be teacher absenteeism, personnel training, among others, as indicated by Carnoy (2005). Future studies should analyze the impact of strikes as well as the effect of teacher absenteeism or, better still, the impact of "closed public schools" in the increase of families' private school choice decisions, especially since 2003.

Both previous evidence that showed families' preferences for private schools because of teacher strikes, and the evidence observed in this study, would indicate that the public school in Argentina experience a problem of "institutional image" for important sectors of society, regardless of the objective conditions and processes of social reality. This, in turn, reinforces the idea "public school = closed school."

Educational policy has, then, a double task: it needs to solve the problem of teacher strikes as a means of improving the institutional image of public schools, and take other actions to transform the social imaginary that associates public schools with closed schools. Working on both aspects, might help to moderate the unprecedented growth of private education in Argentina.

Notas

1 Néstor Kirchner (2003-2007) and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (2007-2011 and 2011-2015).

2 It refers to the days not worked due to teacher conflicts multiplied by the number of teachers supporting the measure (Chiappe, 2011; Etchemendy, 2013.)

3 The labour conflict survey records teacher strikes in all levels and kinds of schools in the education system.

References

Athanasiades, H. & Patramanis, A. (2002). Dis-embeddedness and de-classification: modernization politics and the Greek teacher unions in the 1990s. The Sociological Review, 50 (4), 610-639. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.00401.

Belot, M. & Webbink, D. (2010). Do teacher strikes harm educational attainment of students? Labour, 24(4), 391-406. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9914.2010.00494.x.

Botinelli, L., Herrera, D., Almirón, M. & Stegman, F. (2013). La educación en debate, Le Monde Diplomatique, 12.

Bravo, H. (1996). Una confrontación de relevancia: derecho de huelga vs. derecho de aprender. Buenos Aires: Academia Nacional de Educación.

Carnoy, M. (2005). La búsqueda de la igualdad a través de las políticas educativas: alcances y límites. Reice: Revista Electrónica Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 3 (2), 1-14.

Carter, B. (2004). State Restructuring and Union Renewal: The Case of the National Union of Teachers. Work, Employment, and Society, 18 (1), 137-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0950017004040766.

Chiappe, M. (2011). La conflictividad laboral entre los docentes públicos argentinos 2006-2010. Buenos Aires: Dirección de Estudios de Relaciones del Trabajo, ssPTyEL, Ministerio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social.

D'Aspremont, C. & Gabszewicz, J. J. (1985). Quasi-monopolies.Economica, 52 (206), 141-151. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2554416.

Donaire, R. (2009). ¿Desaparición o difusión de la "identidad de clase trabajadora"? Reflexiones a partir del análisis de elementos de percepción de clase entre docentes. Revista del Programa de Investigaciones sobre Conflicto Social-ISSN 1852: 2262.

Etchemendy, S. (2013). Conflictividad laboral docente. Buenos Aires: mimeo.

Gasparini, L.; Jaume, D.; Serio, M. & Vázquez, E. (2011). La segregación escolar en Argentina. Cedlas, Documento de Trabajo 123.

Gatto, F. & Cetrángolo, O. (2003). Dinámica productiva provincial a fines de los años noventa. Santiago de Chile: Cepal-Eclac.

Gaziel, H. H. & Taub, D. (1992). Teachers Unions and Educational Reform: A Comparative Perspective: The Case of Israel and France. Educational Policy, 6 (1), 72-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0895904892006001005.

Gentili, P., Suárez, D., Stubrin, F. & Gindín, J. (2004). Reforma educativa y luchas docentes en América Latina. Educacaoe Sociedade, 25 (84), 1251-1274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302004000400009.

Gertel, H. R., Cámara, F., Decándido, G. D. & Gigena, M. (2013). Schoolchoice in Latin America: Does migration matter? Instituto de Economía y Finanzas, Córdoba: Universidad Nacional de Córdoba.

Gómez Schettini, M. (2007). La elección de los no elegidos: los sectores de bajos ingresos ante la elección de la escuela en la zona sur de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. En: M. Narodowski & M. Gómez Schettini (eds.) Escuelas y familias. Problemas de diversidad cultural y justicia social. Buenos Aires: Prometeo.

Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states (25). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hoxby, C. M. (1996). How teachers' unions affect education production. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111 (3), 671-718. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2946669.

Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas (2012). Informe de Índice de Desempeño Provincial 2012. Rosario: Fundación Libertad.

Lott, J., & Kenny, L.W. (2013). State teacher union strength and student achievement. Economics of Education Review, 35: 93-103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2013.03.006.

Moe, T. M. (2011). Special interest: Teachers unions and America's public schools. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Morduchowicz, A. (Ed.) (1999). La educación privada en la Argentina: historia, regulaciones y asignación de recursos públicos. Buenos Aires: Inédito.

Moschetti, M. (2013). La expansión de la educación privada en la Argentina (1994-2010). Un estudio sobre el cuasi monopolio estatal del sistema educativo, MA Diss. Buenos Aires: Universidad Torcuato Di Tella.

Murillo, M. (2012). Teachers Unions and Public Education. Perspectives on Politics, 10 (1), 134-136. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1537592711004440.

Murillo, M., Ronconi, L. (2004). Teachers' strikes in Argentina: Partisan alignments and public sector labor relations, Studies in Comparative International Development, 39 (1), 77-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02686316.Narodowski, M. & Narodowski, P. (1988). La crisis laboraldocente, Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de América Latina.

Narodowski, M. (1990) Ser maestro en la Argentina, Buenos Aires: Suteba.

Narodowski, M. & Andrada, M. (1999). Descentralización y desregulación del sistema escolar. Cuaderno de Pedagogía Rosario, 3 (5).

Narodowski, M. & Andrada, M. (2001). The privatisation of education in Argentina. Journal of Education Policy, 16 (6), 585-595. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02680930110087834.

Narodowski, M. (2008). School choice and quasi-state monopoly education system in Latin America: The case of Argentina. En: M. Forsey, S. Davies & G. Walford (eds.) The globalization of school choice? Oxford: Symposium Books.

Narodowski, M. (2011). Cuasimonopolios escolares: lo que el viento nunca se llevó. Educación y Pedagogía, 22(58), 29-36.

Narodowski, M. & Moschetti, M. (2014, julio) ¡Vuelen, blancas palomitas! La caída de la matrícula en las escuelas primarias públicas argentinas. Foco Económico. http://focoeconomico.org/2014/07/15/vuelen-blancas-palomitas-la-caida-de-la-matricula-en-las-escuelas-primarias-publicas-argentinas/.

Narodowski, M. & Moschetti, M. (2015). The growth of private education in Argentina: Evidence and explanations. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 45 (1), 47-69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2013.829348.

Narodowski, M., Gottau, V. & Moschetti, M. (2013). Quasi-state monopoly of the education system and socioeconomic segregation in Argentina. Article prepared for presentation at the 2013 World Education Research Association Focal Meeting, Mexico, November 19th.

Puiggrós, A. (2003). Qué pasó en la educación argentina. Buenos Aires: Galerna.

Rivas, A.; Vera, A.; & Bezem, P. (2010). Radiografía de la educación argentina. Buenos Aires: Cippec.

Scialabba, A. (2006). Evaluación de la educación por parte de la opinión pública y su conformidad con la educación pública y privada en la Cuidad de Buenos Aires, MA Diss., Buenos Aires: Universidad de San Andrés.

Shenkar, M. & Shenkar, O. (2011). Labor conflict on the national stage: Metaphoric lenses in Israel's teachers' strike. Comparative Education Review,55 (2), 210-230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/657973.

Sinclair, J.; Ironside, M. & Seifert, R. (1996). Classroom struggle? Market oriented education reforms and their impact on the teacher labour process. Work, Employment & Society,10 (4), 641-661. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0950017096104002.

Tiramonti, G, & Ziegler, S. (2008). La educación de las elites: aspiraciones, estrategias y oportunidades. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

Torres, C. A. (2008). Después de la tormenta neoliberal: La política educativa latinoamericana entre la crítica y la utopía. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación,48, 207-229.