Relationship Between Group Seating Arrangement in the Classroom and Student Participation in Speaking Activities in EFL Classes at a Secondary School in Chile

Relación entre la organización de sala de clases en grupos y la participación de los estudiantes en actividades de producción oral en clases de inglés como lengua extranjera, en un colegio secundario, en Chile

Relação entre a organização da sala de aula em grupos e a participação dos estudantes em atividades de produção oral nas aulas de inglês como língua estrangeira em uma escola secundaria no Chile

Roxanna Correa1

Emilio Lara2

Patricio Pino3

Tamara Vera4

1 Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción, Chile. Correo electrónico: rcorrea@ucsc.cl

2 International Center, Concepción, Chile. Correo electrónico: laraespinozaemilio@gmail.com

3 Holiday Inn Express Concepción, Chile. Correo electrónico: pjpino@emingles.ucsc.cl.

4 Universidad del Bio Bio, Chile. Correo electrónico: tamiveraa@gmail.com

Artículo recibido el 13 de noviembre de 2015 y aprobado el 5 de agosto de 2016

Abstract

In the Chilean context, classrooms tend to have a vertical distribution of seats and desks, commonly known as rows. This action research aims to investigate the effects of changing this distribution from rows to separate tables in students' participation in speaking activities in EFL lessons. This study was carried out over a month and it consisted of two phases: the first, under the orderly rows, and the second, under the separate-table seating arrangement. Each phase was recorded and a sample of students was interviewed for the analysis of their perception of the two different seating arrangements and their participation in classes. The results showed that separate tables enhance interaction among learners, who had a positive attitude towards the new organization and seemed intrinsically motivated to participate in EFL lessons. However, Spanish was mostly used. Nonetheless, the participants cherished the opportunity to interact with their classmates in a relaxed, inviting environment.

Keywords: Seating arrangement, EFL, interaction.

Resumen

En el contexto chileno, las salas de clases tienden a tener una organización vertical, comúnmente conocida como filas. Este trabajo de investigación-acción busca conocer los efectos de cambiar esta distribución de filas a grupos, en la participación de los estudiantes en actividades de producción oral en clases de inglés. Este estudio fue llevado a cabo durante un mes y comprendió dos fases: la primera, con la sala de clases organizada en filas, y la segunda, en grupos. Cada fase fue grabada y se entrevistó a una muestra de estudiantes para analizar sus percepciones sobre los dos tipos de organización y su participación en clases. Los resultados mostraron que la organización en grupos estimula la interacción entre los estudiantes, quienes muestran una actitud positiva hacia la nueva organización de la sala de clases y parecen motivados a participar, aun cuando mayoritariamente hablaron en español. No obstante, los participantes valoraron la oportunidad de interactuar con sus compañeros en un ambiente relajado y acogedor.

Palabras clave: Organización de la sala de clases, inglés como lengua extranjera, interacción.

Resumo

No chile, as salas de aula têm usualmente uma organização vertical, conhecida como linhas. Esta investigação ação procura conhecer os efeitos ao mudar essa distribuição de linhas para grupos na participação dos estudantes em atividades de produção oral em aulas de inglês. Esse estudo foi desenvolvido durante um mês em duas fases: a primeira, utilizando linhas e a segunda, grupos. Cada fase foi gravada e uma mostra de estudantes foram entrevistados para a análise de suas percepções sobre os tipos de organização e sua participação na aula. Os resultados mostraram que a organização em grupos estimula a interação entre os estudantes, eles exibem uma atitude positiva frente a nova organização da sala de aula e parecem motivados para participar, mesmo se o espanhol foi utilizado a maior parte do tempo. Contudo, os participantes valoraram a oportunidade de interatuar com seus companheiros em um ambiente descontraído e acolhedor.

Palavras chave: organização da sala de aula, interação, inglês como língua estrangeira.

Introduction

The way in which a teacher can manage a class and its possible impact in students' learning behaviour, have concerned educational researchers. Emmer et al. (2011) consider classroom management to be an enduring concept with two distinct purposes: to establish an appropriate environment so that learners can achieve meaningful learning, and to enhance learners' moral and social growth.

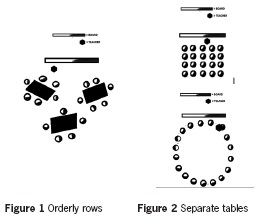

Taking into account Harmer's (2007) conception of seating arrangements and the aims that the current study tries to achieve, two seating arrangements, orderly rows and separate tables, were considered. Consequently, two questions concerning the research problem arise: What aspects of an EFL lesson make students participate more actively in class? What aspects make learners use their mother tongue or the target language when participating in an EFL lesson?

According to Harmer (2007), different types of seating arrangements foster the flow of oral interactions. Hence, if students participate more in class they would be able to improve their language skills, specially speaking, as they are most likely to interact with each other in a more fluent way. This research aims to investigate and describe the existent relation between seating arrangements and students' participation in the Chilean EFL context. The interest of researching this topic is based on the lack of research regarding the effects of seating arrangements in EFL lessons in the Chilean context. Besides, due to the large number of students in classes, the classroom organization mostly used at schools is orderly rows. This kind of organization does not promote students' interaction and participation in class. In fact, some teachers also prefer to keep the classroom this way because it helps them to maintain the class discipline. The Ministry of Education in Chile (Mineduc) has established English oral communication as the main aim in foreign language teaching (Mineduc, 2013), thus teachers have to develop and promote oral communication in class. However, this aim has not been fully accomplished, since the participation of students in the speaking tasks is still very low. Many factors can affect participation in class— number of students, types of tasks designed, students' level of English and classroom arrangement or grouping, among others. This last topic is the main focus of this study.

The main objective of this study is to analyse if different types of seating arrangements hinder or foster the participation of students when interacting in EFL lessons.

Conceptual Framework

This research regards the speaking skill as it aims to study students' oral participation in different seating arrangements. Luoma (2004, p. 20) understands "speaking forms" as part of the shared social activity of talking. Thus, speaking is considered as a form of communicative interaction.

Ur (1997) states that classroom activities that promote learners' ability to express themselves are an important component of a language course. The author also highlights the importance of having in mind topic and task-based activities when achieving speaking in the classroom. A task is goal-oriented; its main purpose is to achieve an objective that is often represented in an observable result accomplished by the participants' interaction. In general, a task can be embellished by the use of a visual aid to support speaking; in this way, topics should be related to the learners' own experiences and knowledge, plus it should represent a genuine controversy so it creates discussion among the group.

Following Luoma (2004), Brown (2001) also highlights the importance of interaction when communicating. The author postulates that interaction plays a crucial role in the modern approach towards teaching a foreign language and pinpoints the importance of negotiation and the exchange of information when interacting.

Not all learners possess the necessary level of proficiency in the target language to constantly participate, let alone engage in fluent interactions with teachers or classmates. Consequently, Oxford (1990) coins the concept of language learning strategies when prompting to give alternatives to those learners who struggle with developing their level of proficiency in English. To Oxford (1990), learning strategies are actions carried out by learners to accomplish a goal. That is, strategies are task-oriented.

Warayet (2011) states that participation is the action by which students engage in oral or non-oral interactions. Students can participate orally by sharing ideas or joining a discussion. On the other hand, students can engage in a non-oral type of participation in the classroom by "using different signals of embodied actions" (p. 44), for example smiling or nodding. The author also states that "participation in the classroom occurs in several ways depending on how interaction is organized" (p. 50). The learning outcome produced through participation in pairs and groups is significant since group work contributes to reduce anxiety and promotes participation. Ur (1997) also mentions some types of interactions, mainly two; active or receptive interaction. In the first one, students speak or write, while in the second one they listen or read.

To promote both participation and the use of the target language in class, Nation (1997) provides some ideas to foster it. The author advices teachers to match the demands of the task with the learner's proficiency. Some students might find discouraging to participate as the influence of the mother tongue can be quite strong, with few opportunities to practice the target language; therefore, he also mentions to change the circumstances of the task. An adjustment in the content of the task might be necessary to make it more comprehensible to the students.

Another factor that may hinder students' participation might be anxiety. In this context, Nation (1997) proposes to change learners' attitude towards English. It is important that learners see how beneficial English can be for them, and also to bear in mind that learners might feel insecure about their performance in the target language. Therefore, taking into account the previous definitions and authors of class participation, it will be defined in this study as the students' active involvement in the learning process, considering not only their contributions to the class aim and topic, but also different ways of interactions among themselves, and with some of the agents that are involved in the students' educational process in the classroom.

The concept of classroom management provides teachers with useful tools to organize lessons. Scrivener (2011) states that classroom management involves the creation of optimum conditions for effective learning without taking into consideration the method, classroom, or students. Moreover, under the umbrella of classroom management, the author highlights the practicality and fruitfulness of using classroom management techniques that help teachers to create most of their teaching space. Marzano, J., Marzano, S., & Pickering (2003) state that no lesson can be developed in an unsupportive context, with lack of resources, let alone with behavioural issues. In this way, classroom management has become an important tool for teachers. The authors conducted a series of studies to observe how classes that applied classroom management techniques improved over the period of a year in comparison to those that did not. Data indicate that classes that used classroom management techniques were likely to have days in which students might behave messily or neatly, yet the number of interruptions during lessons due to disruptive behaviour was diminished. In fact, in the period of one year, classes that incorporated classroom management techniques had about 980 disruptions; on the contrary, classes which did not do so had about 1,800 disruptions. Hence, it can be concluded that effective classroom management is an important factor in classes and has a significant impact on the learners.

This study focuses on one important aspect of classroom management which deals with the physical environment within the classroom; this is the concept of seating arrangement. Larsen-Freeman (1986) highlights the importance that classroom set-up can have upon the development of a class. The author states that when the physical environment of the classroom does not resemble that of a "normal" class, students feel more relaxed as they can, somehow, forget that they are in a regular lesson. In this way, Harmer's (2007) proposal regarding classroom management is related to the distribution of seats and desks, fostering different types of classroom interactions among students individually or in groups. The author proposes four types of seating arrangements as tools for handling a lesson, namely: orderly rows, circle, separate tables and horseshoe.

This study considers two types of seating arrangements proposed and described by Harmer (2007), orderly rows and separate tables. The author states that orderly rows produce a vertical distribution (rows) of the seats and desks in a classroom, emphasizing the role of the teacher and enabling students to pay more attention, but promoting a teacher-centered setting and an asymmetric interaction. On the contrary, Bicard et al. (2012) concluded that orderly rows prevent students from being disruptive and that it helps them to pay more attention; if other students are disruptive, their behaviour does not affect the rest of the class.

Separate-table arrangement, according to Harmer, provides a more informal setting in the classroom. The role of the teacher is to guide and help the groups by walking around explaining, in a more personal and closer manner, what the contents of the class are about. Referring to group work, Meng (2009) believes that this type of work organization increases the speaking opportunities in larger classrooms. He gives three characteristics of group work: (1) it is learner-centered and encourages the use of different types of interactions and tasks; (2) it is quality-oriented, as learners are allowed to engage in fluent interactions and produce coherent utterances, as well as adopt roles and positions which under regular classroom distributions they would not be able to explore; (3) group work is productive. As the focus of the class lies on the learners rather than the teacher, there are more opportunities to use the target language in an oral, practical way within the groups. Separate tables present learners with more language practice, the possibility to engage in creative language use, and the opportunity to develop their oral performance in the target language in a relaxed environment by enjoying the exchange of ideas, opinions and interaction within the groups.

In 2010, Hamzah & Ting conducted an experiment on how speaking activities are developed in small groups. There were three observations conducted and data showed that interacting in small groups fosters higher confidence in students, who are able to express themselves. It was also concluded that students tend to lose the fear usually produced by speaking. Data reveal that students were able to learn how to ask and receive help from their classmates, and that a feeling of being recognized among other students through mutual contribution was created.

Some authors have provided their own preferences about certain types of seating arrangements and how they benefit the students' learning process. Chamot et al. (1999) suggest that working in groups is beneficial for students as they have the opportunity to use the language at a great extent. Cohen (1994) states that, when in groups, every learner has an opportunity to participate in the task. Both Cohen (1994) and Chamot et al. (1999) highlight the importance of delegating work among the groups, as it provides students with the chance to be responsible for their own learning process.

Method

In this study, two types of seating arrangements have been chosen: orderly rows and separate tables. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate both types of seating arrangement.

This is a qualitative study since all the instruments applied to collect the information were used to observe certain patterns of behaviour among the students. Qualitative researchers attempt to observe and interpret a phenomenon, without bias nor narrow perspectives (Chaudron, 2000). Following this author, the qualitative approach is used to understand the different ideas and thoughts people hold concerning a specific issue. These characteristics determine the qualitative nature of this research, which is oriented to go into detail about the participants' experiences and thoughts in specific processes and issues, describing and interpreting the participants' answers.

This investigation was carried out under the action research design, in which the main characteristic, as described by Mills (2007), is to be conducted by teachers. For this action research, two phases were considered; phase 1 involved the seating arrangement in which students are organized in rows as it is common in Chilean classrooms. Phase 2 involved the seating arrangement the researchers considered would be the most suitable in order to improve students' participation in EFL classes: separate tables, in which students are distributed in small groups around the classroom. Thirty eight students within a 15-17 year old range participated in each phase. The participants study at English for Specific Purposes (ESP) School. According to the form teacher, the participants' proficiency level in the target language corresponds to beginners. In this case, ESP is related to industrial minors taught at the state-supported school which can help them in their future workplace requirements. Table 1 shows each phase in detail.

As Table 1 shows, four instruments were used to collect information—2 checklists and 2 interviews. One checklist and one interview were applied in each of the phases of the study. The checklists were designed for teachers to observe aspects regarding student participation during EFL lessons under each seating arrangement. These aspects are: to ask for help to classmates, to ask for help/clarifications to the teacher(s), to make comments related and not related to the topic, to make and share comments with the group, to give opinions when asked and to give opinions spontaneously. The aspects considered in checklists 1 & 2 are pre-determined categories adapted from Araneda et al. (2010) under graduate study. Araneda's research focused on the use of humour to improve students' motivation and participation in an EFL lesson in Chile.

The interviews for each phase were used to obtain students' perception about the specific seating arrangement under which they had been working. The interviews were applied at the end of each phase to a sample of 5 students selected at random. From the data analysis, 4 categories emerged related from the questions for interviews in phase 1 and 2 these are: class participation, aspects that foster and hinder participation, and examples of participation.

The lessons for each seating arrangement phase were recorded for the analysis. The first phase, orderly rows seating arrangement, consisted of two Skill Development Lessons (SDL). In these lessons, the learners were asked to participate and share their knowledge in relation to art (topics such as Shakespeare's best plays). The second phase consisted of two Presentation, Practice and Production (PPP) lesson plans related to daily routines. All of this was in order to follow the teaching criteria according to the High School annual learning program for the English subject.

Results

The analysis of the results evidences the differences between two specific seating arrangements and their relation with students' participation in speaking activities during an EFL class. In the orderly rows arrangement and based on the data presented in Table 1, the participants tend to use their mother tongue (Spanish) more than the target language (English). In 5 out of 7 categories interactions were performed in Spanish. On the one hand, this seating arrangement shows that most of the interactions performed using Spanish focus on aspects such as: asking for clarifications, making comments relatedand not related to the topic, sharing comments with the group, and giving opinions when asked. Few or no interactions are observed in aspects where individual utterances must be performed, for example: asking for permission or asking for help to classmates.

In giving opinions spontaneously, 58.4% of the interactions were performed in English as opposed to the 41.6% of interactions in Spanish. As stated by Harmer (2007), orderly rows foster attention among students; therefore, the participants who gave their opinions out loud must have paid the necessary attention, and must have been confident enough to express their ideas and thoughts in front of their classmates. As the lesson was conducted using orderly rows, the role of the teacher is enhanced, and an asymmetric interaction is created. These results go in the same direction of Bicard et al.'s (2012) findings.

Data show linguistic gaps that stop participants from communicating using the target language. Besides, the effect that rows have upon the development of EFL lessons is clear, as the role of the teacher is enhanced and the learners tend to become rather passive agents.

As it was mentioned above, an interview was designed and applied to make students share and state how comfortable or uncomfortable they are when learning or using English, as well as to provide this investigation with data regarding teaching English while in rows. The data collected are analysed by each category of analysis. Some evidence of class participation is shown in Table 3.

The students agree that participating can be beneficial for future job opportunities. Nonetheless, one of them states that he/she does not participate due to lack of comprehension. Out of the collected data, it can be stated that the results of this research partially match Weaver & Qui's (2005) conception; that is to say, that the learning processes and critical thinking development seem to be occurring thoughtlessly, whereas the benefits regarding practical applications of speaking English seem to be the students' inward urge to use the target language.

Referring to the conditions that foster students' participation, these are detailed explanations—appreciated by the learners, as these allow them to understand the contents more effectively—, previous knowledge, and activities and exercises that match their level of proficiency.

These factors are related to actions that can be carried out during EFL lessons. Consequently, participants might not be aware of how beneficial the pair and group activities proposed by Warayet (2011) can be in the development of their linguistic skills.

Regarding the factors that hinder participation, the linguistic context and the lack of comprehension on the topics are regarded as factors that stop them from participating.

Hence, the results of this category are related to Nation's solutions (1997). Learners would, perhaps, benefit from both an explicit reminder of the benefit of knowing English nowadays, academically and professionally, and some sort of adjustment to the context of the tasks.

In the case of examples of participation, the evidence shows that the most common example of participation is answering in class, followed by asking in class. Raising hands, helping the teacher, giving examples and translating into Spanish are other examples of participation.

Certainty and participation are entwined: if the students know, they participate. Although the types of participation mentioned by Ur (1997) are not mentioned literally by the participants, variations of the types given by the author are mentioned.

In the separate-tables arrangement the number of interactions were registered with the same checklist of the previous seating arrangement. The results of students' participation are presented below.

From the checklist for phase 2, it can be concluded that students still use the mother tongue more than the target language. Nevertheless, phase 2 shows an increase in the amount of interactions in English in different categories, for example: asking classmates for help, asking the teacherfor help/clarifications and giving opinions when asked to do so.

Data also show an overall increase in most of the aspects, mostly in Spanish, yet interactions performed in English show an increase that can be considered to be meaningful regarding the learners' linguistic gaps. Five out of the 7 aspects show an increase in the use of English when interacting. The group distribution provided by the separate-table seating arrangement, given by Harmer (2007) seems to allow learners to interact more fluently with their peers not only in Spanish, but also in English and in a more relaxed manner (Larsen-Freeman, 1986). Nonetheless, a decrease in the giving opinions spontaneously aspect can be observed. As working in groups decreases the fear usually produced by speaking (Hamzah & Ting, 2010), learners are more willing to interact within the groups. This decrease might have occurred because the seating arrangement for this phase makes the learners focus more on the task or topic of the EFL lesson rather than expressing their feelings and opinions in an unplanned manner.

The personal interview applied to the students at the end of phase 2 allows them to state their opinion about the change from rows to separate tables. The data for phase 2 are analysed by each category. The categories are: Perception of group participation, Opportunities to speak English in separate tables, Separate tables and orderly rows participation, Individual and group participation in separate tables. The analysis will be presented by each predetermined category.

Referring to perception of group participation the results show that most of the participants cannot decide if their participation is enhanced or undermined by working in groups.

Although some learners show interest to engage in speaking activities, the loss of focus occurs due to distraction derived from talking to classmates. Regarding their perception, the positive aspects are related to the collaboration among classmates and the drawbacks to conversation with members of the group. Conversation among the group should not be considered as a negative factor; nonetheless, if that conversation was carried out using English, learners would surely benefit from practising the target language orally, even with topics not related to the lesson.

In the case of opportunities to speak English in separate tables, the data collected show that the participants regard this seating arrangement as positive. Oxford's social strategies (1990) are used by the participants as they appreciate working in groups, helping, cooperating and exchanging ideas. In addition, the participants admit that they are comfortable with the idea of being helped and helping others when in groups.

It can be concluded that the results of this category go in the same direction as Harmer's concept of separate-table seating arrangement, as it is considered to be a more informal setting that moves the focus of the lesson from the teacher to the learners. Being surrounded by classmates who are proficient in the language was considered to be important as it will represent a significant contribution to the interaction in groups, as proved by Hamzah & Ting (2010).

The results of class participation in orderly rows and separate tables show that the participants draw several differences from their participation in both seating arrangements. It can be stated that the concepts provided by Harmer (2007) and Warayet (2011) are highly connected and entwined with the learners' opinions and thoughts when assessing their participation in both seating arrangements.

The participants express their preferences to work in groups due to factors such as confidence, concentration, and the exchange of ideas, collaboration when learning and an enhanced sense of comprehension through collaboration. On the contrary, the participants regard nervousness, lack of work, fear to classmates' reactions and lack of comprehension as drawbacks when in rows. The participants indicate that this class distribution —separate tables—allows them to communicate and produce oral utterances in groups during EFL lessons by collaborating, interacting, helping and being helped when needed.

In the category of individual and group participation in separate tables, the participants are aware of the new classroom distribution. Most of them state that a positive change can be observed when in separate tables (lessons tend to flow more smoothly). The participants regard interruptions to the teacher and distraction as negative factors when in separate tables, showing criticism on their own performance in EFL lessons.

To the participants, classes are now learner-centered, quality oriented and productive (Meng, 2009). The participants also regard that EFL classes have a clear structure and more attention can be paid to the teacher.

The comparative analysis of students' participation in orderly row and separate-table arrangement was carried out taking into account the summarized checklist of both phases of the investigation. Both checklists were combined into one general checklist (Table 12).

There is an increase of interactions in L2; nevertheless, it might not be significant. An increase in students' participation regarding the use of the L1 is observed in separate tables, with no participation observed in orderly rows. Larsen-Freeman (1986) states that by creating a physical environment that differs from regular ways of organizing classrooms, learners feel more relaxed and comfortable.

In asking classmates for help to, 0 interactions were observed in orderly rows in both L1 and L2; on the other hand, there are interactions observed in separate tables and 33.3% of them were performed in English. This increase of interactions may be explained by two factors: being this a monolingual class, no further efforts to speak L2 are needed since all the students use the same language; consequently, the familiarity among learners stops them from speaking English. In asking the teacher for help/clarifications, there are interactions in L1, where none of them were performed in L2; however, there are some interactions observed in separate tables and 100% of them were performed in L2. As the separate tables organization enhances group work, the flow of interaction and the sharing of ideas, learners might feel a sense of belonging to a group where they are heard and safe.

When analysing making comments related to the topic, 25% of the interactions in phase 1 are performed in L2; nonetheless, in separate tables only 7.7% of them were performed in English. These results show that, although the number of interactions (in phase 2) increases, only 7.7% of them are performed in L2. Harmer (2007) states that learners participate more when in separate tables. The use of L1 may be explained by lack of confidence in the target language, so Spanish is preferred.

In making comments not related to the topic, all the interactions observed in orderly rows, all performed in L1; the same as in phase 2. Although the results are negative—no interactions in L2—, learners are motivated to fulfil the task even in their mother tongue. Regarding the making and sharing comments with the group category, interactions observed in orderly rows were performed in L1; whereas in Phase 2, 15% of them were performed in L2. It is interesting to notice that the number of interactions within the group increases significantly and there is evidence of interactions in L2. Separate-table seating arrangement seems to promote participation among classmates as well as an incipient participation in the target language.

In giving opinions when asked, 37.5% of the interactions were performed in English, while in separate tables 58.6% of them were performed in English. A notorious increase can be observed in both phases. Regarding the use of L2 when interacting, it is possible to say that in rows, students are not comfortable enough to use English, recurring to their mother tongue when interacting. However, in separate tables, being the flows of communication enhanced through group work, learners are encouraged to express and share their emotions, feelings and ideas in English, as group work facilitates interaction in a more fluent, comfortable, safe way (Meng, 2009). This seating arrangement may help the students to overcome linguistic fears so as to use the target language to express their opinions. The final category is giving opinions spontaneously. There are 58.4% of interactions in orderly rows where 41,6% of them were performed in English; however, 20% of interactions in separate tables were performed in English. A decrease in the use of L2 is observed in phase 2 when compared to phase 1.

As an overall analysis, it can be pointed out that, when interacting in EFL lessons, the participants mainly used their mother tongue rather than the target language in all the categories analysed in the checklists. Additionally, even though an increase could be observed in the students' interactions when being in groups, it did not change the fact that the use of Spanish was more frequent than the use of English in most of the categories. The second phase of this study revealed a slight increase in the use of L2 observed among the participants; as a matter of fact, 5 out of 7 categories in phase 2 show evidence of the use of L2, where no interactions in English were performed during phase 1.

Conclusions

This investigation was established to analyse the relation between separate-table seating arrangement and students' participation in speaking activities in EFL lessons.

Regarding participation with the orderly rows seating, most of the students participated because they considered it beneficial for their future and they thought it was entertaining. Nevertheless, some students say that they only participate occasionally due to lack of comprehension of the instructions in L2 and the task itself.

Although students state different reasons to participate in an EFL lesson in orderly rows, the analysis of phase 1 made it evident that their level of participation was very low. The results showed that the number of interactions among them and with the teacher was little. However, they participate in the categories making comments related to the topic and giving opinions spontaneously. Although they have declared that participation is important because they know that it is beneficial for them, they actually do not participate that often. This may happen because they do not feel comfortable when speaking in English, they can also be afraid of making mistakes, and the time devoted to develop the classes was not enough to promote participation.

When participating in EFL lessons, it was observed that students mainly used Spanish due to their linguistic gaps; nonetheless, when they understood the class contents, L2 was used. The use of Spanish could be related to the level or ability that students need in order to participate in EFL lessons.

Referring to the participants' opinions about the conditions that foster and hinder participation, they mention the following aspects. In the first case, previous knowledge and detailed explanations were pointed out, whereas in the second one behavioural issues, the linguistic context, and the lack of comprehension on the topics were considered as aspects that hinder participation. From the previous examples, it can be concluded that students can add new learning and real comprehension if detailed explanations are given. However, this should happen in an environment of discipline and respect in the class.

As examples of participation, the learners mention the following: answering in class, asking in class, raising hands, helping the teacher, giving examples, translating into Spanish. From the previous list, it might be concluded that the participants relate speaking as the most genuine way of participating, since the first two options (answering and asking) are related to speaking in class. The actions they perform in classes, such as raising hands, helping the teacher, giving examples and translating into Spanish follow the speaking part of the class. Therefore, they realize the importance of the achievement of oral communication as the purest way of participation.

In the case of students' participation in speaking activities with the separate-table seating arrangement in EFL lessons, evidence shows that most of the aspects observed in class increased in terms of the number of interactions performed, especially in the mother tongue, but also in the target language. Thus, it can be concluded that the learners appreciate interacting with their classmates and that they expect EFL lessons to be more learner-oriented, with tasks and activities that allow them to use their oral and social skills as well as improving their proficiency level. Although most of the interactions are performed using the mother tongue, learners still feel an inner necessity to overcome the linguistic gaps that stop them from using the target language at a considerable degree in EFL lessons.

When in groups, the students perceive their participation to be negatively affected by the conversation produced when sitting in separate tables, which is generally performed in Spanish. Although the participants do not seem confident enough to declare whether group participation fosters or hinders the learning of a foreign language, they can clearly distinguish the positive elements it brings—contribution, interaction, help— as well as the negative elements— conversation, distraction and lack of participation— when working in groups. Even though this study was not intended to correlate seating arrangement and English learning outcomes, we may infer that if that conversation was carried out using English, it would represent a more meaningful progress in the learners' linguistic skills in the long term.

The participants assign positive characteristics to the separate-table seating arrangement. They declare to be more relaxed when working in groups, with more opportunities to use English with their classmates. Also, as the participants struggle with their proficiency level in the target language, working in class with proficient speakers might work as a double-edge sword: it can both boost their confidence and improve their linguistic skills or it can make them more dependent on the learners who are proficient, taking advantage of their level, with little or no personal improvement of their linguistic gaps. Even though this phenomenon may happen in any of the two seating arrangements studied, participant students felt more confident to participate in groups regardless their language level.

Regarding the learners' oral performance when in separate tables, the participants state that their linguistic skills in the target language are positively affected by the seating arrangement, as well as the collaboration and communication within the groups. Nevertheless, the results of the checklists for both phases show that the mother tongue, and not the target language, is mainly used when interacting either in rows or groups. Hence, it can be concluded that even though interaction in English can still be observed, the learners are keen on a seating distribution that allows them to work with friends in a more entertaining setting. This arises as a contradiction between what they say and what they actually do. Thus, the separate-table seating arrangement might even be of little help when developing linguistic skills. Learners seem to prefer a distribution that gives them the necessary freedom to discuss and collaborate in EFL lessons, pretending that the interaction within the groups—which is actually normal, casual conversation—, in fact relates to the topics of the EFL lesson.

The learners' attitude towards separate-table distribution is positive, highlighting that it emphasizes their role in the lesson and that it allows them to pay more attention to the teacher, with classes running more smoothly. All the aspects observed in class show an increase in the number of interactions performed both in English and more specifically in Spanish, reaffirming that working in groups proves to be beneficial for collaboration and interaction among learners. Thus, the participants might be fond of this seating arrangement because the pressure of participating individually is lifted, being now the group's responsibility to carry out tasks and activities successfully.

According to the participants, the most meaningful aspects of this new arrangement are the interaction, the collaboration and the discussion that occur within the groups. It is interesting to mention that the participants do not consider the teacher to play an important role when in groups, as their role is emphasized and the teacher's is not.

Concerning the comparison of students' participation in both seating arrangements in EFL lessons, it can be concluded that there is an increase of interactions in the target language in phase 2 when compared to phase 1. This might occur since group work in separate tables promotes the interaction among the participants. Consequently, from this interaction, communication is achieved at a higher extent, an important factor when learning a foreign language.

There is an increase in the students' participation; however, this increase is mainly in L1. The use of L1 may be explained by the lack of confidence of the students in the target language, so Spanish is preferred. Another reason could be that the lack of comprehension on the topics affects their contribution to the class and lowers their desire to participate. Although the results show little interaction in L2, learners are motivated to fulfil the task even in their mother tongue. This might occur as separate tables enhance the flows of interaction and the sharing of ideas. In this way, learners might feel a sense of belonging to a group. Separate-table seating arrangement could promote participation among classmates as well as an incipient participation in the learners' target language. Therefore, a social connection might be needed if speaking is expected to be achieved in EFL lessons.

Regarding the relation with the teacher in phase 1 in contrast with phase 2, it can be stated that participants try to speak English with their peers, but not with the teacher. Perhaps they feel secure when talking to their classmates, but not to the teacher, as they may be afraid of the teacher's opinion regarding their proficiency level. Likewise, they might think that the teacher is going to correct them in front of their peers, who could make fun of them.

A decrease in giving opinions spontaneously can be seen in phase 2. This means that learners are more likely to give spontaneous opinions in orderly rows than in separate tables. It might be possible that their attitude changed in phase 2 because they feel peer pressure to be accurate when giving their opinions about a topic. Besides, they may not want to feel embarrassed if they make a mistake. In phase 1, their opinions are more personal than collective, hence their peers' opinion regarding mistakes is not that important.

The main aim of this study was to analyse the differences between orderly rows and separate-table seating arrangement and the students' participation in speaking activities during EFL lessons.

Further research can be carried out on what activities can match each seating arrangement, making EFL lessons successful, enriching and linguistically developing experiences, with a significant impact on the students 'proficiency level in the target language.

The concept of participation in EFL lesson can also be studied in a more specific manner or narrower perspective. It was noted by the researchers that the participants are aware of the benefits of knowing English for future job opportunities: in this way, studying in depth how participation can positively affect the learners' level of English can help teachers to adapt the contents to fit the students' real needs and interests in the Chilean context. Studying in depth the motivation of students in EFL lessons can help teachers to handle new, more realistic ways to tackle behavioural issues in EFL lessons in the national milieu, and it can also help teachers to boost the actual use of English in Chilean classrooms.

References

Araneda, J. et ál. (2010). Propuesta metodológica de intervención basada en el uso del humor, como estrategia para mejorar la participación oral de alumnos de primer año de enseñanza media en el subsector Inglés en un Colegio particular subvencionado en Concepción (tesis de pregrado). Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción, Chile.

Bicard, D. et ál. (2012). Differential effects of seating arrangements on disruptive behavior of fifth grade students during independent seatwork. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45(2), 407-11.

Brown, H. (2001). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy. United States: Longman.

Chaudron, C. (2000). Contrasting approaches to classroom research. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of language learning. Second Language Studies, 19(1), 1-56. Avaliable on line at http://www.hawai.edu/sls/uhwpesl/19_1/chaudron.pdf.

Chamot, A. U. et ál. (1999). The learning strategies handbook. New York: Longman Press.

Cohen, E. (1994). Designing group work: Strategies for the heterogeneous classroom. New York. Teachers College Press.

Emmer, E. et ál. (2011). Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues. New Jersey: Routledge.

Hamzah, M. & Ting, Y. (2010). Teaching speaking skills through group work activities: A Case study in SMK Damai Jaya. Fakulti Pendidikan, Universiti Teknologi: Malaysia.

Harmer, J. (2007). How to teach English. United Kingdom: Pearson Education Limited.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (1986). Techniques and principles in language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Luoma, S. (2004). Assessing speaking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marzano, J., Marzano, S., & Pickering, D. (2003). Classroom management that works. United States: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Deve.

Meng, F. (2009). Encourage learners in the large class to speak English in group work. College English Department: Xuchang University.

Mills, G (2007). Action research: A guide for the teacher researcher (3rd Ed.), Handbooks. New Jersey, Columbus, Ohio: Pearson Education Inc.

Ministerio de Educación Chile. (2013). Bases curriculares: idioma extranjero inglés. Autor.

Nation, P. (1997). L1 and L2 use in the classroom: a systematic approach. TESL Reporter, 30, 2, 19-27.

Oxford, R. (1990). Language learning strategies. United States: Heinle & Heinle.

Scrivener, J. (2011). Learning teaching. The essential guide to English language teaching. United Kingdom: MacMillan Education.

Ur, P. (1997). A course in language teaching: practice and theory. United Kingdom. Cambridge University Press.

Warayet, A. (2011). Participation as a complex phenomenon in the EFL classroom. Retrieved from https://theses.ncl.ac.uk/dspace/handle/10443/1322 on September 3rd, 2013.

Weaver, R., & Qui, J. (2005). Classroom organization and participation: college students' perceptions. The Journal of Higher Education. 76(5), 570-600.